Chaturanga

The majority opinion among historians of Chess is that it began as a game of Indian origin called Chaturanga. This name was Sanskrit for four arms.

The chatur part means four and is related to our word quarter, while the anga part means arms and is used in this context to mean arms of the military, just like we use arm

in terms like army

and armed forces.

According to H. J. R. Murray, the word chaturanga became the regular epic name for the army at an early date in Sanskrit.

(A History of Chess, Kindle Loc 907) The game was a simulation of war, in which each arm of the military was represented, these being chariots, cavalry, elephants, and infantry. Besides these, there was a king and his advisor. The game was played on an 8x8 board called an ashṭāpada, which was borrowed from an earlier game that was likely a race game.

What is taken to be the earliest reference to the game comes from the Vasavadatta, which is generally taken to be from the 7th century, though it's possibly even older. In translation, the line that is allegedly about Chaturanga reads, The time of the rains played its game with frogs for chessmen which, yellow and green in colour, as if mottled with lac, leapt up on the garden bed squares.

But this reference is not clearly about Chaturanga. The word translated as chessmen

just means game pieces, and saying that the frogs are yellow and green in colour, as if mottled with lac

actually suggests that each frog was spotted or blotched with two different colors, not that some frogs were yellow and some green, as if they represented two sides in a game of Chess. Besides that, there were earlier games played on the same board as Chaturanga, not to mention other earlier games played on boards with squares.

The earliest Sanskrit mention of Chaturanga by name is from the Harshachārita, a biography of emperor Harsha written during the 7th century. Describing the peaceful times during his rule, it says, Under the monarch only bees quarrel in collecting dews; the only feet cut off are those in metre; only ashtapadas teach the chaturanga.

The ashtapada is the 8x8 board the game was played on, and this line is using the word chaturanga

to refer both to the army and the game of chaturanga. Basically, it is saying that Harsha's time was so peaceful, people were learning about warfare only from a game designed to simulate warfare. This line established the existence of a board game based on the four parts of the Indian army that was played on an 8x8 board, but it didn't explain how the game was played.

In a Persian text Murray called the Kārnāmak and dated to 600 A.D., there is a mention of King Ardashīr being good at chess (chatrang). This may not establish the existence of the game in Ardashīr's lifetime, which was from 180-242 AD, but it does help establish the existence of the game at the time of its writing.

The most detailed early reference comes from the Persian work Murray identifies as the Chatrang Nāmak. This account, though largely legendary, identifies the game as being of Indian origin and names the pieces, though it doesn't describe the rules or how the pieces move.

Because of the dearth of Sanskrit writings on Chaturanga, the original game may be lost to history, and knowledge of the game comes secondhand, mainly from Muslim sources. What follows are different accounts of the game from different historians of Chess. They are given in chronological order, except that the most recent is given with the earliest, because they give the same account of the game.

H. J. R. Murray's Account / Harry Golombek's Account

Murray's account of Chaturanga, provided on page 3 of A Short History of Chess, and Golombek's account, provided on pages 15-19 of Chess: A History, agree in every particular. Notably, Golombek contributed to a 1963 reprint of Murray's book, and so would have been familiar with it when he wrote his own history in 1976.

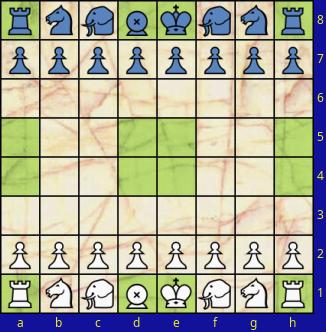

The board was uncheckered, and it had markings on the space which are colored green in this diagram. These markings were apparently inherited from an earlier game played on the same board, and they had no role in Chaturanga.

Regarding the setup, Murray notes that one of the players would place his King in one of the two center squares, and the other player would place his King in the same file at his end of the board. Since the boards were not checkered, there was no hard-and-fast rule about which spaces each player should begin the King and Minister on, such as the modern Queen on her own color rule. Needless to say, it changes nothing essential about the game to play it one way or the other. All it would affect is the notation used, and since we have no recorded games prior to the Muslims learning of the game, it would appear that the Indians who played Chaturanga were not notating or recording their games.

Like the King in Chess, the King (called Rāja) moves one space in any diagonal or orthogonal direction to a space not attacked by an enemy piece. The game was won through checkmating the King or through baring it. On page 6, Murray mentions a Muslim master who noted that the Indians consider stalemate a win for the player who is stalemated. Golombek reports the same rule on page 19, saying The game was also won for the side that was stalemated.

Like the Ferz in Shatranj, the Minister (called Mantri), moves to any diagonally adjacent space.

Like the Alfil in Shatranj, the Elephant (called Hasti or Gaja) moves two spaces diagonally, leaping over the intervening space.

Like the Knight in Chess, the Horse (called Ashwa), leaps directly to a space at the opposite corner of a 2x3 rectangle.

Like the Rook in Chess, the Chariot (called Rat⋅ha), moves along a rank or file over empty spaces.

Like the Pawn in Chess, the Foot-soldier (called Padāti), moves one space forward without capturing or one space diagonally forward to capture. Unlike the Pawn in Chess, it does not have a double-move, and when it reaches the last rank, it promotes to a Minister.

Henry A. Davidson's Account

In 1949, Henry A. Davidson described Chaturanga differently in a book also called A Short History of Chess. Differences from the account of Murray and Golombek follow.

Like the King in Chess, the King (called Rajah) moves one space in any diagonal or orthogonal direction. According to Davidson, notions of check and checkmate were introduced by the Persians, and Chaturanga was won by capturing the opponent's King. Davidson agrees with Murray that the game could be won by baring the King. He does not mention the rule that stalemate was a win for the player stalemated, and given that his account allows Kings to move into check, he probably didn't think that stalemate was part of the game.

Like the Silver General in Shogi, the Elephant (called Gaja) moves one space diagonally or one space vertically forward.

Regarding the setup, Davidson notes that the King and the Counsellor (as he calls the Minister), go in the center, but he doesn't note whether each piece faces the same type of piece in the same file or whether King and Councellor face each other in the same file. In other respects, Davidson's account follows Murray's.

John Gollon's Account

In 1968, John Gollon described Chaturanga in Chess Variations: Ancient, Regional, and Modern. With one exception, he agreed with Murray on the naming and movement of pieces, but he differed from Murray in setup, Pawn promotion rules, and winning conditions.

In addition to moving like the King in Chess, the King (called Raja) may make a Knight move once during the game. It loses this privilege if it is checked. Gollon also reports, The bare king rule is unknown for this game.

He agrees with Murray and Golombek that stalemate was a win for the player stalemated.

Unlike Murray and Golombek, Gollon places Kings at e1 and d8 and Ministers at d1 and e8. This has the effect of allowing Ministers to move along what would be spaces of the same color on a checkered board, which allows the Minister from each side to capture the other.

According to Gollon, Pawns promote on the last rank to the piece originally occupying the space reached, promotion is restricted to captured pieces, and a Pawn may not advance to a space on the last rank unless there is a captured piece of its type for it promote to. One consequence of this is that a Pawn may never promote on e1 or d8.

Summary

In every way that Davidson's account or Gollon's disagrees with that of Murray and Golombek, the other one doesn't. Davidson gives different powers of movement to the Elephant, and he denies that check and checkmate are part of the game, but Gollon does not. Gollon provides different rules for Pawn promotion, and he denies the bare king rule, but Davidson does not. So, every particular of the Murray/Golombek account is favored by at least three out of four Chess historians. Furthermore, Davidson and Gollon have not documented their claims. Murray, however, does give reasons for some of his claims.

Regarding the movement of the Elephant, Murray writes,

The strength of the chess Elephant, however, was glaringly inadequate, and so we find at a later date Indian attempts to strengthen the Elephant's move. One attempt, recorded c. A.D. 850, gives the Elephant a leap over a non-diagonal adjacent square into the one beyond – the complement of the original move which increased its strength about 50 per cent. A second attempt was more durable; it is first mentioned by Rudrata (ante 900), again by al-Beruni (1030), and exists today in the chess of Further India. It gives the Elephant a move to any adjacent diagonal square or to the square immediately in advance: this nearly trebled the value of the piece. (p. 5)

While none of them cite a Sanskrit document detailing the full rules of the game, and we might never know exactly how the game was originally played, it appears that the Murray/Golombek account is the most authoritative account we have of this game. Their approach, which has seemed reliable, is to assume that the game is like Shatranj except where differences have been noted by early Muslim writers on the game.

Equipment

You can play this game with a regular Chess set. For a more authentic look, you may wish to include Elephant pieces from the Elephant & Hawk Musketeer Chess variant kit. Two kits will give you two of each color. The link will bring you to a page with more photographs and links for purchasing this and other piece kits.

Computer Play

Use Zillions of Games to play Gollon's interpretation of this game! If you have Zillions of Games installed, you can download chaturanga.zip and play it.WWW page created: 1995.